Defamatory material is the essence of any defamation claim, but what is more important is how each element of defamatory material is satisfied. In defamation claims, the element of identification is crucial in bringing a cause of action because if the Plaintiff is not identified than they are not defamed. Identification is one of three main elements in establishing whether a publication is, in fact, defamatory. Furthermore, there are a few components to consider when determining whether identification of a Plaintiff has been established, including whether the Plaintiff has been identified directly or indirectly, the relevance of the Defendant’s intention at the time of publication, and other circumstances that may arise.

Direct Identification

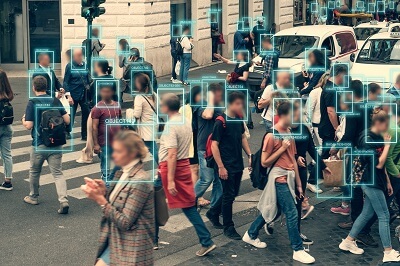

There are two ways that a Plaintiff can be identified in a publication: directly and indirectly. While it may not always be the case, for a Plaintiff to be identified directly they must be named in the publication. In other circumstances, the Plaintiff can be identified by their address, title, or photograph. This list is not exhaustive. There is some controversy regarding whether naming a Plaintiff and publishing their photograph or image without naming them are the same. Justice Hunt in Barbaro v Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd[1]insisted that they were different while in Dwek v Macmillan Publishers Ltd[2], the Court contended that there is no difference in logic or fact that the Plaintiff be identified by photograph or name. Direct identification of a Plaintiff in a publication means that they would be identified with the natural and ordinary meaning of the publication. For example, in Consolidated Trust Co Ltd v Browne[3], the Plaintiff was identified in the publication by his title in office as the ‘Prime Minister of Australia‘, without further naming him. In comparison, establishing direct identification is much easier than indirect identification.

Indirect Identification

Indirect identification of a Plaintiff in a publication requires more analysis. In Consolidated Trust Co Ltd v Browne[4], Chief Justice Jordan explained that the less indicative the description of the Plaintiff, the less likely it will be to prove identification. Often, indirect identification is where the Plaintiff has not been named in the publication, rather there is some inference to the Plaintiff where he or she could be identified. In such circumstances, to establish identification, the publication must refer to something that connects to the Plaintiff by way of innuendo. Subsequently, the Plaintiff must particularise extrinsic facts that can demonstrate that he or she was identified in the publication. This requires the test that the ordinary, reasonable reader with knowledge of these extrinsic facts would be able to identify the Plaintiff. A Plaintiff can call witnesses to express that they were able to connect the Plaintiff to the publication, to strengthen the argument of identification. Examples of indirect identification include phone numbers, initials, caricatures, or paintings. Due to the contention of photographs directly identifying a Plaintiff, such a situation would require that one or more people connected the photograph to the Plaintiff[5].

Relevance of Intention to Identify

In defamation claims, whether a Defendant had the intention of identifying the Plaintiff or not is irrelevant[6]. The reasoning behind this is that, should a Plaintiff be identified in a publication, a Plaintiff will suffer harm to his or her reputation regardless of whether a Defendant intended to refer to a Plaintiff. Unfortunately, in either situation a Defendant can be held liable for a publication.

A ‘Same Name’ Plaintiff

Where a Defendant does not have the intention of identifying a Plaintiff, they may intend to identify another person with the same name as the Plaintiff. Again, in such circumstances a Defendant can be held liable for defamation should the Plaintiff be reasonably identified from the publication. In Lee v Wilson & Mackinnon[7], a prisoner gave the Defendant information that ‘Detective Lee’ of the Motor Registration Branch accepted bribes in a police inquiry. The Defendant published the information provided by the prisoner inaccurately. At the time of publication, three officers with the surname ‘Lee’ were serving in the police force. Subsequently, two of the officers commenced defamation proceedings and the Court ruled in favour of them. The Court held that where a publication is capable of identifying more than one person, the Defendant will be held liable. Intention in such circumstances is not relevant.

A Fictitious Plaintiff

Similarly, a Defendant who publishes material referring to a fictitious character can be held liable if a real Plaintiff can be identified from the publication. Effectively, the Plaintiff can call a witness to provide evidence of identifying the Plaintiff with the publication. Again, intention of the Defendant is irrelevant in this situation.

The case of E Hulton & Co v Jones[8], was one of a plaintiff barrister, named Thomas Artemus Jones and was known commonly as ‘Artemus’. A newspaper published an article about a fictitious character by the same name, who ‘misbehaved’ with another woman at a festival, whilst married. While the publisher of the article provided evidence that the character was not a reference to the barrister, the barrister was able to prove, by calling five witnesses to establish that they had identified the barrister as the character in the article. Further, the barrister was a long-time contributor to the newspaper. The Court awarded damages to the Plaintiff concluding that the Defendant was reckless in the publication.

Identification of Groups or Classes

When referring to defamatory statements against a group or class of people, the determining factors of identification becomes more complex. In such circumstances, the Plaintiff’s personal reputation must be reasonably capable of being identified by the publication that is made against a group or class of people to which the Plaintiff belongs to. This would then allow the Plaintiff to sue for damage of their personal reputation[9]. For example, in the case of Mann v Medicine Group Pty Ltd[10], the Plaintiff was a specialist medical practitioner, and the Defendant was Medicine Group Pty Ltd who published to the Australian Dr Weekly a letter. The letter contained various defamatory statements, including claiming that doctors breached the Hippocratic oath for money by bulkbilling patients. Justice Wilcox claimed that the publication was not reasonably capable of identifying the Plaintiff, as it applied to all Australian bulkbilling doctors. Contrastingly, in the case of David Syme & Co Ltd v Lloyd[11], cricket captain, Clive Lloyd sued a newspaper for publishing the headline, “Come on dollar, Com on”, insinuating that the Plaintiff engaged in match-fixing. While the Plaintiff was not named in the article, the Court found that the ordinary, reasonable reader would be able to identify the Plaintiff as the captain of a cricket team.

Throughout the years, the Courts have yet to consider an approach towards identifying a group or class of people and who is capable of a successful defamation claim. For instance, in Pryke v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd[12], the Court held that in two defamatory articles referring to unnamed commissioners of the Industrial Relations Commission of South Australia, the four commissioners were reasonably capable of being identified. Conversely, in McCormick v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd[13], the Court found that defamatory statements against one of three unnamed partners of a private investigation firm, were not reasonably capable of being identified. More recently, in Christiansen v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd[14], the Court held that a newspaper article publishing defamatory statements about casino managers, was liable as the statements created suspicions to arise over all of them.

Prior and Subsequent Publications to Establish Identification

In defamation matters, generally identification of a Plaintiff must be made during publication, whether that be directly or indirectly. If a Plaintiff is identified indirectly, then the Plaintiff can use prior publications with extrinsic facts known at the time of publication. Accordingly, this can be used to determine “the Public Mind”[15] regarding the Plaintiff’s identity. Conversely, subsequent publications are less likely to be relied upon as identification must be established at the time of publication[16]. In the case of Ware v Associated Newspapers Ltd[17], the Defendant published an article where the Plaintiff was not identified and the next day published a second article identifying the Plaintiff. The Court held that the first article and second article were relevant enough to identify the Plaintiff. In Baltinos v Foreign Language Publications Ptd Ltd[18], the Court found that the Plaintiff could rely on subsequent publications as the Defendant’s matter invited the audience to refer to the subsequent publication. Ultimately, the Courts have agreed to rely on subsequent publications for identification, with careful examination of the situation.

Conclusion

Overall, the element of identifying a Plaintiff requires that they be reasonably capable of being identified by a publication. A Plaintiff can be identified either directly or indirectly, and different situations may arise within that. Whether a Defendant is liable depends on whether a personal reputation is damaged in any given situation.

At Harris Defamation, we can help you through any defamation process. Whether you are being defamed or have defamed another, we can assist.